Mix tape

Sometimes I go to yard sales to buy cassettes compiled by people who are complete strangers to me. You see something that has 'Marty's Mix' scrawled on it in ballpoint pen. You take it home and you don't know if it's going to be US post-punk hardcore or Kenny Rogers. Whatever it is, though, I know I'm getting a slice of someone's life. Cassettes are the only format that can give you that.

- Thurston Moore of band Sonic Youth (Quoted by Pete Paphides)

A Mix Tape is an amateur-created audio cassette music compilation, compiled of different songs from different albums (usually taken from other tapes, from LPs or the radio). While sometimes mix tapes contained songs from various albums by the same artist, most mix tapes were also collections of songs by different artists. Most mix tapes were inherently personal, either kept for oneself, or given to a friend or lover. However, as will be discussed, mix tapes had special meaning in hip hop culture, in which they were inherently public media forms.

Beginning in the late 1960s, with the emergence of the Philips compact cassette in 1963 and the development of Japanese-made cassette players and recorders in the mid to late 1960s, mix tapers began to challenge the notion of the single-artist album by taking on the role of the creator (Millard 315-6). As scholar Rob Drew notes, “Rather than conforming to artistic intention and industry practice, mixers treated the album as an open work and took the selection and ordering of songs into their own hands” (535). The mix tape thereby enabled people “to make their own personal soundtracks and compilations.“ (535)

As we shall see, the mix tape as it is defined here would disappear in the mid to late 1990s with the emergence of the compact disk, and later the digital playlist. While these musical forms have inherited tropes of the original mix tape form, there are fundamental differences between the experience of creating, listening to, and receiving an original cassette mix tape versus these new "versions".

Contents

Technological History

The Compact Cassette

Following in the tradition of its predecessors, the reel-to-reel, the compact cassette was a device introduced primarily for the purpose of personal and workplace related recording (316). As is indicated by its name, the compact cassette was revolutionary due to its transportable size: small enough to fit into a pocket, and yet able to hold up to 45 minutes of content on each side.

Introduced by Philips in 1963, the compact cassette sold poorly in it's first year, selling only about 9,000 units. As a result, Philips did not declare the cassette as proprietary technology, and instead, encouraged other companies to license the use of the technology. All that Philips required was that all other manufacturers adhere to the Philips standard, so that all manufactured cassettes were equally compatible (317).

As a result of this opening up, by the mid 1960s, a variety of cassette playing devices were being manufactured by various Japanese corporations, notably Panasonic and Norelco. Norelco introduced the first cassette player/recorder, "The Norelco Carry-Corder", powered by flashlight batteries and weighing approximately 3 pounds. By 1968, approximately eighty five different manufacturers had sold over 2.4 million cassette players and recording devices across the globe. Moving in the 1970s, Millard notes, "The Philips compact cassette became the standard format for tape recording by the end of the decade" (317).

The only thing holding the compact cassette back, however, was its sound quality. Unlike the LP record, it was a low fidelity medium with poor sound quality, disturbed by loud tape hissing. Over the years, various companies developed different methods of improving the sound quality. Ray Dolby, an employee of the Ampex Corporation managed to devise improved methods for reducing the noise of magnetic tape. The Dolby A system worked by emphasizing certain high frequencies during the recording process, and then de-emphasizing these frequencies during playback, resulting in less tape "hiss" (318). Manufacturers of magnetic tape, particularly Japanese companies like Sony, Denon and TDK, developed new magnetic materials to coat the plastic tape, thereby accommodating more magnetic information (318). Consequently, the reduction of tape hiss as a result of Dolby's system, combined with "the higher-frequency response of chrome and metal particle tapes" brought the tape into the high fidelity realm, and gained it the respect of audiophiles (319).

As a result of these improved technologies, record companies began releasing albums on compact cassette. Cassettes could be easily and attractively packaged, they were small and durable, while exceeding the playing time of a long playing record. By the late 1970s, the cassette tape had begun to challenge the disc in total sales, and by the early 1980s, the ratio of vinyl to cassette was around 6:4 (320).

Mix Tape Recording Technology

Following the emergence of the cassette tape and early cassette recorders and players was the introduction of more sophisticated home cassette recording technologies by Japanese manufacturers in the 1970s, specifically those that allowed cross media recording.

By the 1970s, the affordable combination record player/radio systems came with a built in cassette player, which could record any output out of the unit, either off the radio, or off a record (319). Simultaneously, the cassette was becoming a more and more popular way to purchase commercial music. Music listeners wanted a way to record music not just from vinyl to cassette, but from audio cassette to audio cassette. This was altered with the emergence of the double or dual cassette deck (see Patent) allowing the user to record from one pre-recorded tape to a blank one in the same unit. This technology would later be developed into the popular, portable "boom box" form, which allowed your tape-to-tape reproduction studio to be taken with you at all times (Millard 322).

By 1982, more than twenty million audio recording devices were believed to be imported into the United States, and it was estimated that approximately sixty percent of American households had at least one tape recorder (Jeffords PAGE). Almost everyone had become a home tapper, and the listener's relationship with music was experiencing fundamental changes.

"Home Taping is Killing Music"

Before there was music downloading and Napster, there were cassette mix tapes. While tape was certainly not the first home recording technology (Edison's wax cylinder phonograph was recordable), it was certainly the first reliable and mainstream one (Walker).

By the 80s, when cassette ripping was becoming increasingly popular, record labels began to fight back, accusing home tapers of killing the music industry (rhetoric which sounds familiar in the post-digitization era). Beginning in 1982, the recording industry began to lobby for surcharges on blank tapes, and even experimented with anticopying technology which would be encoded on vinyl LPs (Walker).

The cassette and cassette equipment manufacturers retaliated with a strong counter lobbying movement, however, and with Sony at the lead (who was simultaneously fighting the Hollywood studios over it's Betamax player), the counter lobbyists won, upholding "a consumer's right to copy for personal use" (Walker).

Home taping was never "killing music", as the record companies claimed it was. People continued to purchase music despite the new cassette recorders, in fact, prerecorded cassettes and discs sold in increasing quantities (Millard 327) It was the way they interacted with that music, as we shall see, that fundamentally changed.

Types

Personal

Most of this discussion of the audio cassette mix tape focuses around the personal mix tape. I use the term "personal mix tape" not to refer to mix tapes solely made for ones self (although those are common), but rather, to refer to mix tapes that are not intended for widespread public listening and consumption (ie in a club, in the street etc). Personal mix tapes are usually bound up in ideas of personal expression: of one's ideas, thoughts or feelings for another. The new cassette technology empowered individuals to reject the one way producer-consumer relationship in order to express their own individuality. "The mixtape is both personal and an expression of technological will to power", Paul Hegarty notes, "an intervention that occurs not outside but against and within power relations that structure music listening" (Hegarty). The compact cassette mix tape encouraged individuals to harness the creative form of music, and utilize it for their own personal expression.

DJ and Hip Hop Mix Tape

For my purposes, I will be largely focusing on the personal mix tape form, as the mix tape has gone on to carry significantly different meanings in the contemporary hip hop community. Nonetheless, it is important to understand how the roots of the term mix tape in hip hop and dj culture, were not so far off from our understanding of personal mix tapes.

Like the personal mix tape, the hip hop tape was a collection of different songs by different artists, recorded onto an audio cassette. A 1974 Billboard article described the phenomenon of the hip-hop DJ mix tape..

"Tapes were originally dubbed by jockeys to serve as standbys for times when they did not have disco turntables to hand. The tapes represent each jockey's concept of programming, placing, and sequencing of record sides. The music is heard without interruption. One- to three-hour programs bring anywhere from $30 to $75 per tape, mostly reel-to-reel, but increasingly on cartridge and cassette."

Billboard Magazine MORE HERE

Mix Tape Theory

The User Art form?

Predigested cultural artifacts combined with homespun technology and magic markers turn the mix tape to a message in a bottle. I am no mere consumer of pop culture, it says, but also a producer of it. Mix tapes mark the moment of consumer culture in which listeners attained control over what they heard, in what order and at what cost . - Matias Viegener, Writer and Critic (Quoted in Moore, 35).

Matias Viegener wrote the above in a short piece entitled "The mix tape as a form of American Folk Art", and the title of the piece speaks to Veigener's understanding of the mix tape. For Viegener, mix tape making, like folk art, is not high brow, it is not museum art, it is creative works by the people for the people. Nonetheless, there are elements of the mix tape that make it seem inherently creative, and almost artistic in nature.

Firstly, the creation of the mix tape is inherently about self expression (Jansen 45). Describing his mix tape constructing a mix tape as a teenager, chef Pat Griffin said: "these were the purest moments of my affliction, constructing my own private radio station, one that could match my teenage psychosis riff for riff, made for no other consumption than mine"

Secondly, the creation of a mix tape on audio cassette involves implicit skill and technique that when excecuted well, some consider to be an artform. In an article entitled, "Love me, Love My Mix Tape" published in Newsweek, Jessica Bennett recalls her experience making a mix tape off the radio:

It took hours to make: every free moment curled by the boombox, the local radio station's song-request line set to speed dial, the volume knob turned loud enough to hear, but quiet enough not to wake Mom and Dad. Then, finally, the master product: a flawless combination of Alanis Morissette, Nirvana and Boyz II Men decorated, doodled on and packaged in that familiar square case that would become the soundtrack to a fleeting eighth-grade romance . (Bennett)

Almost every recollection of mix tape making emphasizes both the technique involved in making the tape, and the sheer amount of time invested in its creation (Jansen 45). This idea of technique and timing as value is an idea echoed by Pete Paphides: "In the past when you compiled a tape for someone, the time spent making it was central to its perceived value. You would also have a fairly good idea that each track followed on smoothly from the last one because the compilation would have been made in real time" (Paphides). The fact that one literally had to sit with the recorder, pressing play and stop, and syncing up each song, meant that the process of making a mix tape was a fundamentally engaging one. There was also the constraint of having to fit all songs within the two distinct sides, A and B, presenting opportunities for intensive structuring of the mix (Jansen 48)

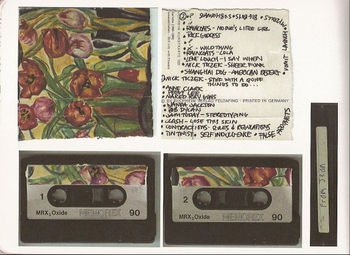

Thirdly, the creation of a mix tape was not merely the paring together of songs. Instead, it involved what Jansen calls "the quest for cohesion", not only in its musical selections, but also in its physical encasing and it's liner notes (46). A mix tape should be " a work in its own right rather than as a collection of disparate elements" (47). Cohesion, is usually attained through a variety of constraints; the creator must follow a particular theme or idea, and he/she must create a mix with interesting "flow" (47).

While of course, not all mix tapes possess the same caliber of creative self expression resulting in a unified whole, and indeed, mix tape making is more a folk-art than any kind of high-art, there seems to be a striving for something inherently artistic, something creative in mix tape creating, that is fundamental to it as a media form.

Romance, Friendship and Gift Culture

One of the fundamental elements of mix tapes, particularly the representation of mix tapes in popular culture, relate to mix tapes as gifts.

Mixtape as Memory

Death of the Mix tape

Contemporary Incarnations

The Mix CD and Digital Playlist

Commercial Use of Mix Tape

References

Davis, Brian Joseph. "Fade Out". Utne Reader. Topeka: Jul/Aug 2006 Iss 136 p 30-31

Hegarty, Paul. "The Hallucinatory Life of Tape". Culture Machine, Vol 9 (2007). <http://www.culturemachine.net/index.php/cm/article/viewArticle/82/67>

Jansen, Bas. "Tape Cassettes and Former Selves: How Mix Tapes Mediate Memories". Sound Souvenirs. Ed. K. Bijsterveld & J. Dijck. Amsterdam University Press

Jeffords, Edward Alan. "Home Audio Recording after Betamax: Taking a Fresh Look". Baylor Law Review. 855 (1984)

Paphides, Pete. "Thinking inside the (plastic) box: Still cherished by mix-tape romantics, the cassette isn't ready to die, says Pete Paphides". The Times. London (UK): Dec 18, 2009. p. 8

Millard, Andrew. America On Record: A history of recorded sound. Second Edition. New York: Cambridge University Press,2005.

Moore, Thurston. Mix Tape: The Art of Cassette Culture. New York: Rizzoli International, 2004.

Drew, Rob. "Mixed Blessings: The Commercial Mix and the Future of Music Aggregation". Popular Music and Society; Oct 2005; 28, 4; Research Library pg. 533

Walker, Rob. "Hit Rewind". The New York Times 25 April 2010